Twitter, Lies, and COVID-19: Defeating the Coronavirus Infodemic

By Dr. Cathia Jenainati, dean of the School of Arts and Sciences and Dr. Haidar Harmanani, SoAS associate dean

Did you hear the one about the Coronavirus having originated in bat soup[1] which is a popular dish in Wuhan province? Or, the advice that “If you can hold your breath for 10 seconds, then you don’t have the Coronavirus”[2]?

Did you receive the news that “the Coronavirus spreads through petrol pumps”? or that it “can be cured by ingesting fish-tank cleaning products[3]”?

We have all been swamped by various types of news purporting to reveal the nature of the virus, its origins and its symptoms. Scores of professed cures are shared on social media outlets every day, some harmless: “take oregano oil, vitamin C and salt water”[4] while others are outright dangerous “Just drink bleach[5]!”

News creation and consumption has been changing since the advent of social media. According to Statista[6], an estimated 2.95 billion people in 2019 used social media worldwide. The number is projected to increase to 3.43 billion in 2023. One remarkable statistic is around the continually changing demographic of news consumers. Since 2014, researchers have noticed that “young people are active news consumers, with particular attentiveness to breaking news”[7], while in 2018 the Pew Research Centre reported that “most Americans continue to get news on social media, even though they may have concerns about its accuracy.”[8] Numerous surveys have been undertaken to capture the online behavior of news consumers worldwide, and the trend seems to be that social media platforms are highly influential when it comes to acquiring news stories, for the majority of people. In a large-scale study conducted by Ofcom[9] in 2019, it was shown that “Half of the adults in the UK now use social media to keep up with the latest news.”

In the Middle East, a similar trend is noticeable. According to The Arab Weekly[10] “Nine in ten young Arabs use at least one of the major social media channels daily.” Their analysis shows that the particular choice of social media outlet varies by nation. Egyptians seem to prefer Facebook while users in Saudi Arabia and Turkey favor Twitter. Perhaps the most interesting fact about the preponderance of social media use in the MENA region comes from Google who suggested that “Millenials in MENA are twice as likely as their global counterparts to post content online and show others how to do things online.”

The data, across continents, is comparable. There is strong evidence that people of all ages are accessing social media outlets, not only to communicate and play online games, but also to acquire news and share it with others. The latter behavior is unique to social media stories. For, unlike hard copy newspapers, and unlike television and radio news programs, social media offers the facility of instant forwarding of any news story. The forwarding is immediate, and it can snowball to become a trending topic that reaches millions of individuals. Furthermore, in the act of sharing news on social media, a false sense of ownership is bestowed on the sharer who is able to edit, exaggerate or otherwise contribute to the story, thereby making them at once consumer and producer of news. It is at this crucial point that our research positions itself.

If, 2.95 billion people used social media in 2019, then it is fair to argue that these platforms have helped to democratize news production and dissemination. The counterargument is that social media has become a breeding forum for false and fake news. This is in fact one of the main conclusions reached by a group of researchers at the School of Arts and Sciences at the Lebanese American University focusing on the social media misuse of the novel COVID-19 virus in order to spread fake news, and even at times to gain access to host machines.

The LAU study, led by Associate Professor of Computer Science Azzam Mourad in collaboration with Computer Science graduate student Ali Srour investigated the social media coverage of the COVID-19 virus and concluded that conspiracy theories and propaganda are spreading faster than the COVID-19 pandemic itself, creating an infodemic.

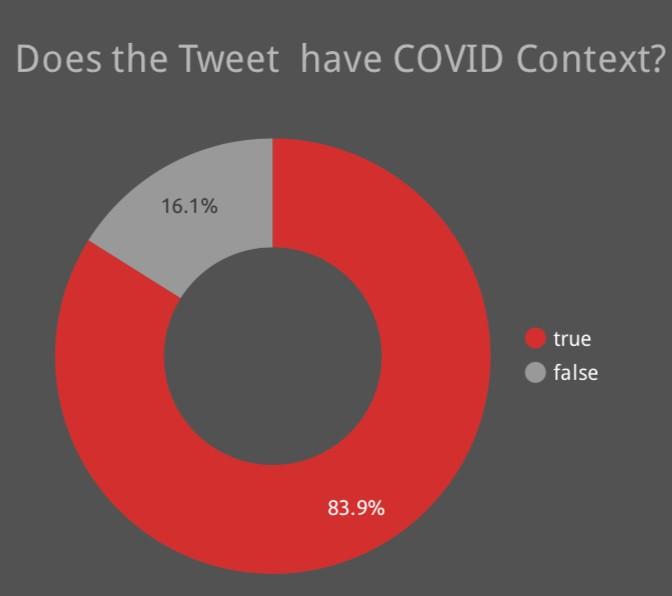

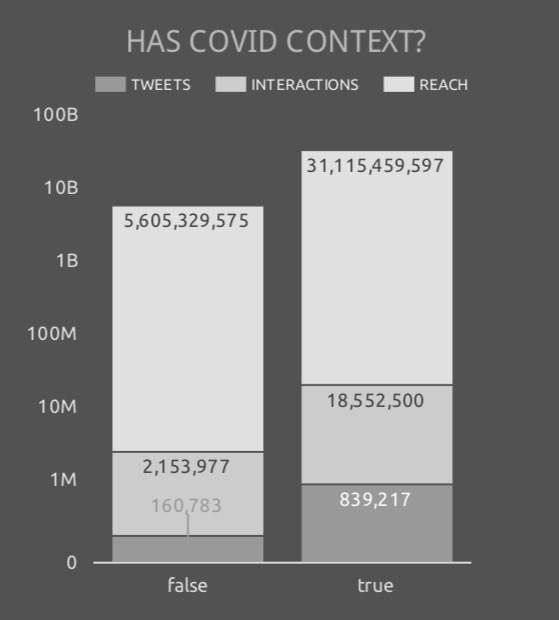

The study tracked 1 million tweets initiated by 288K unique tweeters over a two-month period and found that most of the related tweets, 53.5 percent, used the COVID_19 hashtag. A further analysis on the context of these tweets concluded that 16.1 percent are not in fact related to the COVID-19 pandemic and exploited the hashtag for advertisement purposes such as selling fake coronavirus cures as well as propagating malicious links and contents including cyberattack on critical information systems. Although the percentage appears to be low however, the 16.1% has an impact of 5.6 billion Reach counts and may project to much more given the actual number of tweeters and interactions.

Figures, 1 and 2

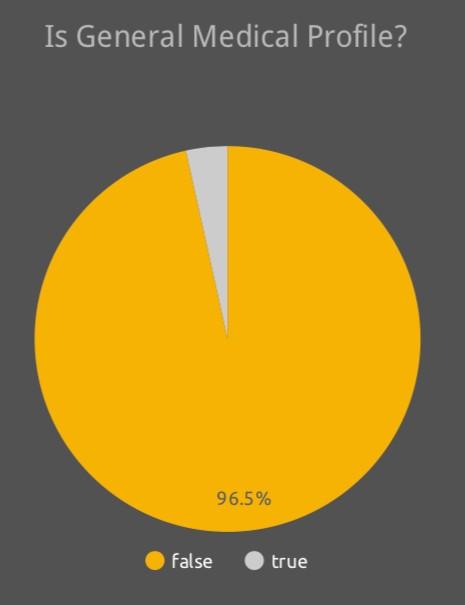

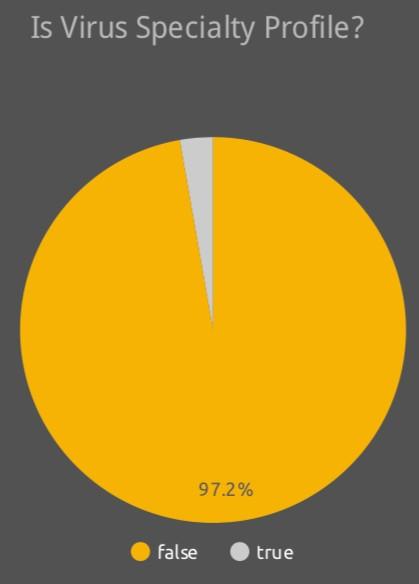

As for the 83.9 percent, the LAU study further analyzed and classified the profiles of the tweeters. The study concluded that only 3.5 percent and 2.8 percent of the COVID-19 tweeters are medical and virus experts, respectively. As for the other 93.7 percent with a Reach counts of more than 30 billion? The study did not find any reliable evidence that confirms their credibility. In other words, 93.7 percent of the COVID-19-related tweets might be propagating unreliable medical information.

Figures, 3 and 4

The Solution?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), we are fighting an infodemic that is making it difficult for people to find reliable resources for information. The UN is stepping up their communications efforts through global cooperation and viral acts of humanity. Although some are promoting the Chinese model of censored contagion, the solution is for health authorities, governments and social network stakeholders to formulate regular responses to the infodemic using a strategy of active engagement and communication with those who are spreading inaccurate stories in order to gain a deeper understanding of how infodemic spread.

In some countries, government is setting up official units mandated to combat the spread of inaccurate and unsubstantiated news. In the UK, for example, “a rapid response unit within the Cabinet Office is working with social media firms to remove fake news and harmful content.”[11] In India, “the central government ordered telecom companies to make an audio clip explaining coronavirus as a caller tune for mobile phone users.”[12] Elsewhere, we see leaders urging the public to be vigilant and more discerning of the quality of news they receive on their phones.

Perhaps the most powerful solution to tackle this, or any future infodemic, lies with the consumers themselves. Taking personal responsibility of the role that each person plays when they receive, read, edit, comment and then forward a piece of information that originates on a social media platform is, arguably, the most impactful intervention to debunk the myths and falsehoods that are generated on an hourly basis. But while this point may be easier written than done, there is value in examining it further.

On the one hand, we know that millennials are active users of social media. That is good news, to some extent, because this is the generation that has “grown up digital”. Consequently it is the segment of the population that could respond actively to governmental guidance on personal responsibility and the importance of personal restraint. On the other hand, we know that the trend of increased participation in the use of social media covers billions of users who grew up receiving mostly government-sanctioned news, or else knowing exactly where the bias of newspapers and broadcasting stations lies. That generation has been taken aback by social media. And it remains in awe of its power, its reach, its availability and the possibilities it affords for communicating with others instantly. Targeted campaigns must be launched to educate anyone whose date of birth precedes the year 2000 to educate them on the social responsibility that they bear whenever they partake in perpetuating stories on Twitter or any other platform.

On this point, we conclude our brief paper which has established the wide reach of trending stories on Twitter, and we gesture towards the next piece of research that begs to be conducted and which should explore, quantitively, the direct impact that individual trending stories has on the population. Until then, and whenever we are tempted to “re-tweet” we ought to be mindful of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s wise words: “If we do not wish to be ruled by a coercive authority, then each of us must rein himself in. A stable society is achieved by conscious self-limitation.”

[2] https://www.itv.com/news/2020-03-23/these-are-some-of-the-fake-news-and-hoaxes-being-shared-about-coronavirus-and-what-you-can-do-to-stop-their-spread/

[5] https://www.thedailybeast.com/qanon-conspiracy-theorists-magic-cure-for-coronavirus-is-drinking-lethal-bleach

[7] American Press Institute, “Social and Demographic Differences in News Habits and Attitudes” (March 17, 2014) https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/publications/reports/survey-research/social-demographic-differences-news-habits-attitudes/

[8] Elisa Shearer and Katerina Matsa, “News use across social media platforms 2018” (Sept 10, 2018) https://www.journalism.org/2018/09/10/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2018/

[9] Ofcom is the UK government’s regular for the communications services that are used by the public on a daily basis. This study was published in July 2019 and can be accessed in full at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/research-and-data/tv-radio-and-on-demand/news-media/news-consumption

[10] The Arab Weekly “Social Media Use by Youth is rising across the Middle East” (26 January 2020) https://thearabweekly.com/social-media-use-youth-rising-across-middle-east

[11] BBC, “Coronavirus: Fake News Crackdown by UK Government” (30 March 2020) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-52086284

[12] Kunal Purohit, “Misinformation, fake news spark India coronavirus fears” (10 March 2020) https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/03/misinformation-fake-news-spark-india-coronavirus-fears-200309051731540.html